It has long been reported that plants respond to sound and the belief that plants can respond to music has taken root in the popular imagination. We’ve all heard stories of farmers and hobbyist alike serenading their plants and producing miraculous results. But do these experiments have any scientific underpinnings? Unsurprisingly, there is very little scientific research into the subject and a serious dearth of scientific proof that plants can respond to sound, let alone music. However, scientists have been repeatedly surprised in what plants can respond to and it has been discovered that plants have at least 20 different senses. Will hearing be the next?

The misconception that plants can respond to music has its origin in poorly carried out scientific experiments, wishful thinking, the mixing of science and spirituality of the new age movement, and misreporting by the media.

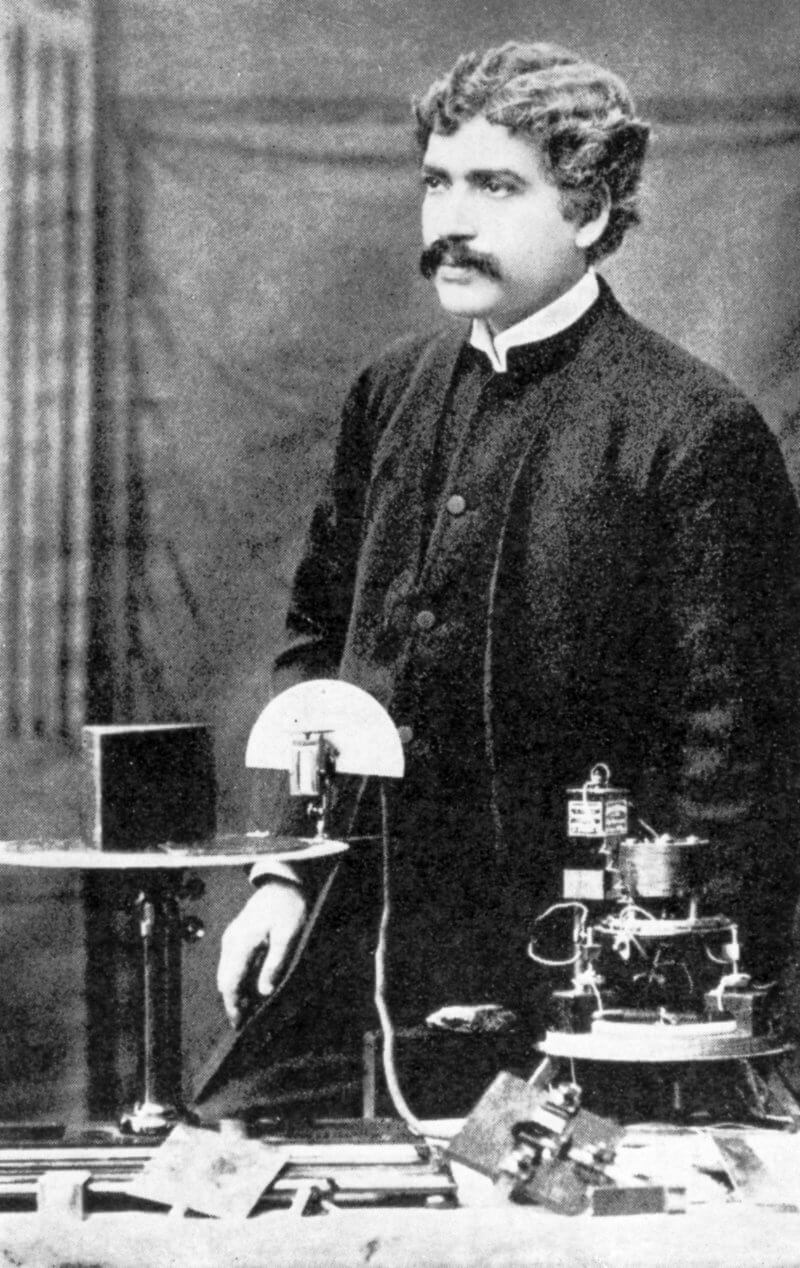

Experiments documenting the effects of music on plant growth date back to at least 1962 when T.C. Singh, head of the Botany Department at India’s Annamalia University, reported significantly improved growth of balsam plants exposed to music. His ideas were inspired by the Indian plant physiologist, Jagadish Chandra Bose, who spent a lifetime investigating the responses of plants to environmental stimuli, concluding that plants could both feel pain and understand affection. Research continued with Luther Burbank, an American botanist and horticulturalist, who concluded plants possess 20 sensory perceptions. All of this was preceded by Charles Darwin’s early investigations into plant perception, who once played the bassoon to a Mimosa plant, but concluded it had no effect.

The findings of the above researches were compiled into The Secret Life of Plants (1973), by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird. The book, considered a piece of fiction by many scientists, was underpinned by quacky new-age ideas and took into account many questionable experiments and studies including the work of Dorothy Retallack, who eventually published the The Sound of Musical Plants in the same year.

Retallack, an undergraduate student in music, had to take a biology module as part of her course and decided to investigate the effects of music on plant growth. Convinced that rock music was having a negative effect on the nation’s youth, she decided to test how the different genres would affect plants. Unsurprisingly, she found that rock music did have a highly negative effect on plants, causing them to wilt. By contrast, Ravi Shankar’s Indian sitar music led them to thrive. The experiment was fraught with shortcomings with a small sample size (5), insufficient replicates, and plants located in different environments.

The Secret Life of Plants sold well and many of its ideas would seep into the popular imagination. The book would even get its own motion picture adaptation, soundtracked by Stevie Wonder, released in 1979. The score would be expanded and released in the same year as Journey Through “The Secret Life of Plants”. It was made with the film’s producer describing the experiments to Wonder, the final result a mix of instrumental and pop songs, with the best the catchy Outside My Window.

Playing music to plants was a phenomena that preceded the book and musicians even composed music to be played to plants such as Mort Garson’s Mother Earth’s Plantasia. Described on the linear notes as “warm earth music for plants…and the people that love them”, the album was produced using the Moog synthesizer, of which Garson was an early adopter.

So, why do people consistently report music improves plant growth? A good answer comes from a series of experiments described in Peter Scott’s Physiology and Behaviour of Plants. The first experiment tests whether rock or classical would produce faster germination vis-a-vis a control exposed to no music. The results show that while both rock and classical increased germination against the control, there is no difference between the genres. This may seem surprising, but the second experiment adds an extra control – a small fan that blows away the heat generated from the speakers. The results show that there is no difference in germination between the plants exposed to music and the control. The faster germination originating from the heat of the speakers, not the plants responding to music.

Another possible explanation is that those who play music to plants are more likely to create conditions suitable for plant growth. Even if music has no effect on plants, the extra care and attention will, whether it be sufficient watering or correcting nutrient deficiencies for example.

Is there any reason to believe that plants can respond to sound? According to Daniel Chamovitz, professor of Life Sciences at Tel Aviv University, it is possible that we are simply performing the wrong tests. Evolution takes place extremely slowly and music is not an evolutionary pressure on plant development. We need to first identify the ecologically relevant sounds that could affect how a plant develops and adapts to its environment.

Furthermore, it is not necessary for organisms to have complex ears to pick up sound waves as a range of morphological features will suffice. Snakes, for example, use their jawbones to pick up ground-borne vibrations and deliver acoustic information to their mechano-sensory system. The ability to respond to sound may be useful for plants as it allows energetically cheap signalling that could be used for an array of functions.

There are some promising experiments that appear to document plants responding to sound, although increased repetition and further studies will be needed to convince the wider community.

One experiment found that the roots of maize plants grew towards the source of sound, especially at frequencies between 200 and 300Hz and emitted acoustic emissions themselves. Another found that specific frequencies between 125Hz and 250Hz made certain genes more active, while frequencies at 50Hz made them less active. Lastly, one experiment found that plants would respond to vibrations mimicking the sound of a caterpillar’s jaws chewing, producing a class of chemicals poisonous to caterpillars as a response.

So, what is going on here? These experiments indicate that plants respond to and emit sound when it is defined as vibrations that travel through the air or another medium. These sounds may be not be recognisable to us, but it is sound nonetheless. Ultimately, the identification of the mechanisms through which sound is detected and emitted will be key in transforming the hypothesis into a veritable theory. The how explaining the why.

–

Jorge works in the Primrose marketing team. He is an avid reader, although struggles to stick to one topic!

His ideal afternoon would involve a long walk, before settling down for scones.

Jorge is a journeyman gardener with experience in growing crops.