Cherry trees are an important, multifaceted part of Japanese culture with its blossom (sakura) featuring on everything from political and military insignia to popular designs and coinage. Despite this, cherry tree blossom is fleeting with the flowers’ lifespan usually lasting only a week. It is this exact quality that explains the trees’ enduring appeal – the symbolic representation of the transient nature of life, and beauty itself, which is celebrated with the popular custom of hanami, in which Japanese picnic under the bloom.

Over the centuries, the sakura’s meaning has evolved, but also become tightly interwoven with Japan’s cultural fabric. Not merely because of its beauty, but because political groups have sought to use the symbol for their own ends. Originally, the cherry blossom was connected to Japanese folk religions due to its phenology – that is its capacity to flower during the changing of the seasons. Agricultural communities came to believe that the falling petals transformed into the deity of rice paddies. It was in this period that trees began to be transplanted into towns.

712 AD gives us the first written reference of cherry blossom. The Empress Gemmei, fearful of neighbouring Tang Dynasty’s power, sought to compile an account of Japan’s unique development and distinctiveness from its neighbours. This compilation, Kojiki, raised the status of the cherry blossom (in contrast to China’s plum blossoms), beginning the custom of hanami in which nobles and commoner alike celebrated under the blossom.

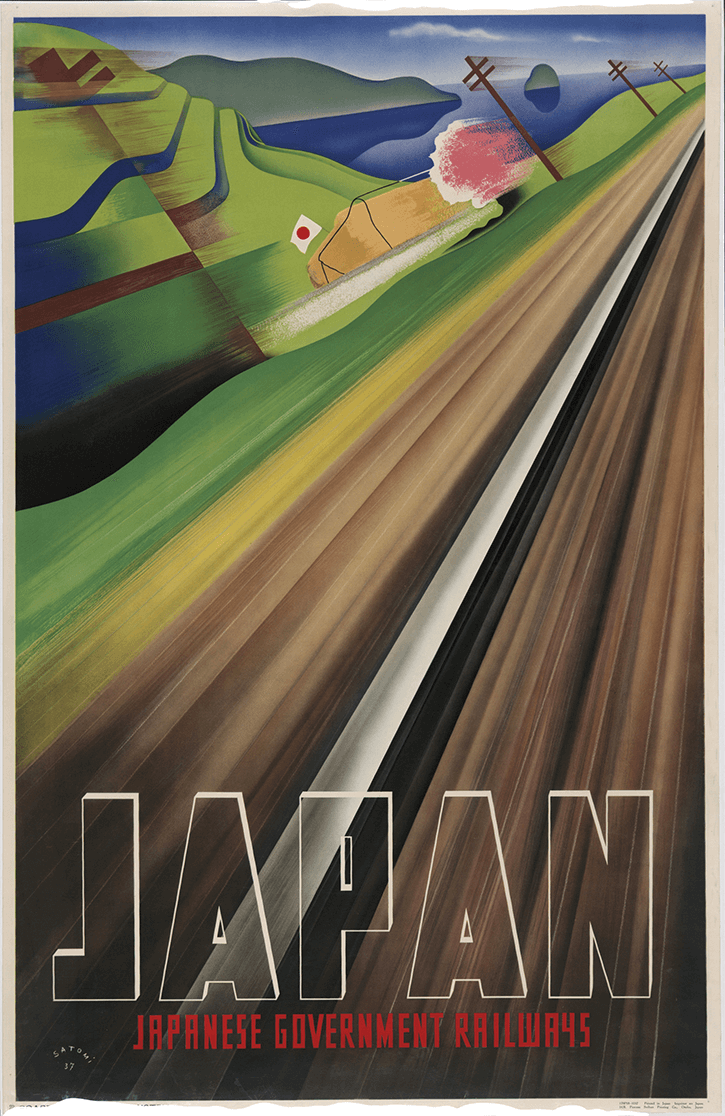

The Heian period (794-1185) saw the spread of new sects of Buddhism throughout the Japanese landmass and witnessed the development of the concept mono no aware. The term is culturally significant and helps explain Japan’s love for the cherry tree blossom. It refers to an awareness and acceptance of impermanence as a reality of life. This is perhaps best demonstrated through this segment of Japanese television. Throughout the centuries, representations of sakura also proved highly popular in Japanese art as demonstrated in the art-deco masterpiece celebrating speed and modernity below.

The 12th century saw the rise of the samurai, whose power was consolidated with the establishment of a feudal system under the shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo. Much like lords in Europe, samurai were provided with estates in return for military service and were motivated by their own code of chivalry, known as bushido. Part of the bushido’s code was an identification with cherry blossom as it fell at the moment of its greatest beauty, symbolising an ideal death. The samurai decorated their equipment with emblems of cherry blossom.

The Meiji restoration of 1868 saw the end of the shogunate and the establishment of the Empire of Japan. It began a process of centralisation, which reclaimed governing authority from the shoguns and samurai. Newly established, the Japanese Imperial Army took over the defense of the state, resulting in samurai losing their social status and privileges. Keen to reconfigure the Bushido code, Japanese were deemed of noble character, able to face death without fear and willing to die like beautiful falling cherry petals for the Emperor. In 1969, the Emperor set up the Yasukuni Shrine as a memorial devoted to fallen soldiers. It is lined with cherry blossoms, supposedly to console soldier’s souls.

From the beginning of the Meiji period and until the end of WW2, the Japanese government sought to use cherry blossom symbolism as a means to bind the country together. After witnessing the occupation and division of neighbouring states, including the once mighty China, the state felt it necessary to create a strong, shared national identity to prevent against fracture. This establishment of the national essence of Japan is known as kokutai.

In 1910, the city of Tokyo sent 2,000 trees to the U.S. as a gift to President William Howard Taft, who had previously spent time in the Far East. These died on the way, but were replaced with a second batch that were planted along the Potomac and grounds of the White House in 1912. These trees proved popular and celebrations would eventually evolve into the annual Cherry Blossom Festival. Interestingly, cuttings from these trees would be sent back to Japan to restore the original collection, which were badly damaged in WW2.

In WW2, the Empire again sought to utilise the Bushido code to inspire their troops. They revived the medieval proverb “hana wa sakuragi, hito wa bushi” that means as the cherry blossom is the first among flowers, so the warrior was first among men. In 1944, the Empire resorted to kamikaze operations in an effort to save Japan from defeat. Tokkotai, or kamikaze planes, were painted with cherry blossoms and pilots affixed branches to their uniforms.

In March 2011, a tsunami struck Japan, devastating its coastal communities. The aftermath was documented in the Oscar-nominated “The Tsunami and the Cherry Blossom” that includes a Japanese man’s reflections on the strength of the cherry tree to live on in spite of the devastation. The tree constituted an inspiration to continue living as if “the plants are hanging in there, so us humans better do it too”.

Today, cherry blossom helps mark the beginning of the financial and academic year in Japan, although the date of flowering is dependent on temperature. In recent decades, cherry blossom has flowered increasingly early – a fact put down to global warming. The blossoms are big business for Japan with the cherry blossom season attracting thousands of tourists. The countdown is televised with the Cherry Blossom Forecast documenting the advance of the blooms from south to north. Retailers cash in by offering a assortments of cherry blossom goods including many culinary delights such as sakura pepsi, crisps and tea.

And of course, there is hanami that is still widely celebrated throughout Japan. The custom takes two forms: one that involves partying (sakura parties) and the other that involves a more traditional observance of the blossoms (umeni). Like Christmas, hamani celebrations often involve special dishes and drinking of alcohol. Hanami at night is known as yozakura and many public places will hang up lanterns to facilitate such events.

So to summarise, cherry blossom are a huge part of Japanese culture representing the bravery of soldiers, the philosophical notion of mono no aware, peace and friendship with other countries, celebration and Japan itself.

–

Jorge works in the Primrose marketing team. He is an avid reader, although struggles to stick to one topic!

His ideal afternoon would involve a long walk, before settling down for scones.

Jorge is a journeyman gardener with experience in growing crops.