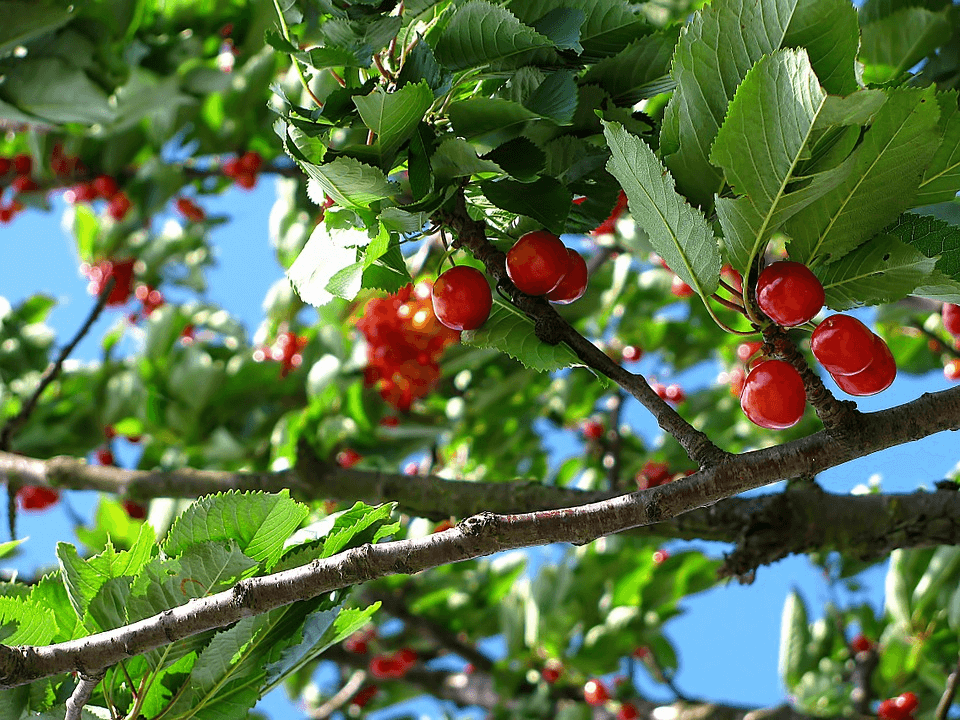

Pollination is important as without it trees will not produce fruit. Most trees require insects to transfer pollen between male (anthers) and female structures (stigma), ensuring fertilisation. Some trees, however, can self-fertilise. Without fertilisation, trees would be unable to propagate and the production of fruit (seeds) would be useless. In the case of cherry trees, some are self-fertile and others are self-sterile, depending on the variety.

Self-sterile cherry trees require another variety flowering at the same time to ensure fertilisation. They are henceforth put into flowering groups from 1 (very early) to 6 (very late). A cherry tree can be partnered with a cherry that is plus or minus 1 (+-1) its own group.

To make matters more complex, pollen can be transferred from one variety to another and be rejected. This is usually because varieties are too closely related. They are henceforth put into groups (from 1-15 or A-O). A variety must therefore be in a different group within plus or minus 1 (+-1) flowering group.

Thankfully, this is where universal donors come in that will pollinate any cherry tree within plus or minus 1 flowering group. We henceforth recommend, you pair one of these self-fertile varieties with another. As previously mentioned, some cherry trees are self-fertile and do not need to be paired with another. However, they do benefit from cross-fertilisation, so for heavier crops we recommend pairing.

Another factor you need to consider is the date of the last frost in your location. Frost can be extremely damaging to blossom and will reduce your crop. It can be useful to choose trees in late flowering groups if you have a late last frost. Your locations date can be found using this resource online. It should also be noted that bad weather such as rain and wind will prevent pollinating insects from visiting your blossoms and could also reduce your crop. To combat this, you can use frost protection or move potted plants indoors temporarily.

It is important to note that cherry blossom trees will not fertilise edible cherry trees, although acid cherries will. As cherry trees are somewhat common, it is possible that another tree could fertilise your own tree. As bees forage widely, a tree within 30m could fertilise one of your own, although it is simpler to plant another within the immediate vicinity. If you believe pollination has been disrupted, you can pollinate yourself by using a paintbrush and transferring pollen from one plant to another.

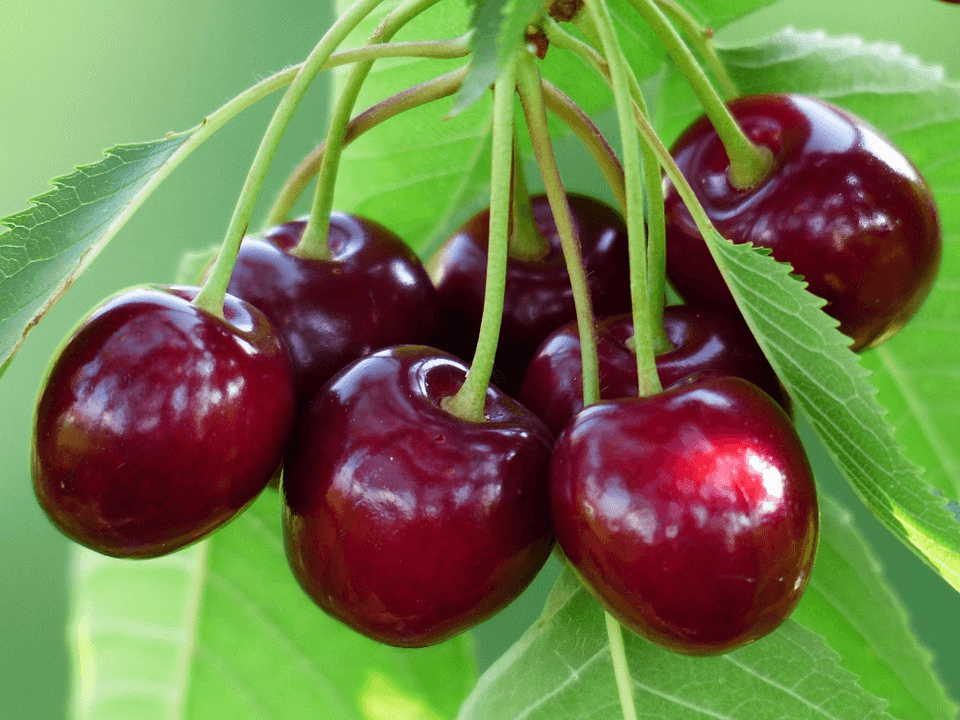

So why bother with multiple varieties? Firstly, just like apples, different varieties produce different tasting fruits, owing to their sugar content, acidity and tannins. Some are suitable for cooking and others best eaten straight off the tree. Secondly, growing multiple varieties allows you to ensure a steady supply of cherries throughout the warmer months. Thirdly, you can never know how well a particular variety will do in your garden, so it is always worth experimenting. Lastly, some varieties are resistant to cracking, which usually occurs during summer rains. Others are more productive producing larger crops and larger size fruits, which provide more bang for your buck.

As a rule, acid cherries are predominantly self-fertile, while sweet cherries are self-sterile. Now without further ado, here is an overview of the different varieties’ characteristics. We have highlighted our recommendations in bold.

Universal Donors (Self-Fertile)

Group 2

These cherries will fertilise any variety in flowering groups 1-3.

- Celeste: Large red/black cherries with excellent flavour. Naturally compact and great for pots.

- Hartland: Naturally compact and great for pots. Productive.

- Lapins / Cherokee: Large mild-tasting dark red fruits, which are resistant to cracking. Highly productive and naturally vigorous. RHS Award of Garden Merit.

Group 3

These cherries will fertilise any variety in flowering groups 2-4.

- Petit Noir: Large black heart-shaped fruits. Naturally compact and great for pots.

- Skeena: Late ripening and perfect for extending the cherry season. Large, well balanced fruits.

- Sweetheart: One of the best flavoured cherries that are best eaten straight off the tree. Uneven ripening allows one to avoid a glut.

Group 4

These cherries will fertilise any variety in flowering groups 3-5.

- May Duke: Tangy versatile fruit, great for eating fresh and making jams. Cross between an acid and sweet cherry.

- Morello: Acid cherries that are perfect for cooking. RHS Award of Garden Merit awardee.

- Nabella: Acid cherries that are great for jams, pies, and liqueurs. Competitor with Nabella. New introduction.

- Stardust Coveu: Very sweet white cherries. Great flavour and firmness. The only self-fertile white cherry.

- Stella: Large blood-red fruit. Very juicy and sweet tasting. Highly productive, but sensitive to cold. RHS Award of Garden Merit awardee.

- Sunburst: Very productive with large, firm fruit, which are resistant to cracking.

Self-Sterile

Group 2

- Burlat: Dark, red sweet cherries. Easy to grow.

- Merton Glory: Large, red fruit flushed with white. Very tasty but not suitable for storage.

Group 3

- Merchant: Large black/red cherries with good flavour. RHS Award of Garden Merit awardee.

- Sylvia: Compact with upright growth. Similar taste to Stella. Suitable for containers.

- Summer Sun: Great tasting dark red fruit. Suitable for northern areas of the UK. RHS Award of Garden Merit awardee.

- Van: Reddish black, sweet cherries. Superb flavour.

- White Heart: Large yellow-red fruit. Good resistant to bacterial canker.

Group 4

- Colney: Large burgundy coloured fruit. Resistant to bacterial canker and RHS Award of Garden Merit awardee.

- Karina: Hard and tasty. Perfect with meringue and ice-cream. Not widely available in the UK.

- Kordia: Large black glossy fruit. Resistant to cracking and disease resistant. RHS Award of Garden Merit.

- Regina: Mild sweet fruit, which are resistant to cracking. Balanced flavour.

- Sasha: Dark red cherries that are sweet and juicy. Heavy cropping.

Group 5

- Bigarreau Napoleon: Another “white” cherry with pale golden white flesh. Firm-fleshed with a sweet tangy taste.

Scientific Appendix

Want to know why cherries are self-sterile? Read on if you dare.

Pollen compatibility is genetically controlled by a single gene with alternative forms (alleles). These alleles have been given names S₁, S₂, S₃, S₄ and so on. One variety may have S₁ and S₂, another S₁ and S₃ and so on. These are put into compatibility groups with group 1 containing S₁S₂ varieties, group 2 S₁S₃ varieties, and so on.

Pollinisation involves the transfer of pollen from the male anther to the female stigma. In cherries the pollen contains one allele, while the stigma contains both allele. Alleles are self-incompatible, so a pollen grain with the allele S₁ can’t fertilise any stigma with allele S₁. Thus, varieties within a compatibility group can’t pollinate one another, but varieties in different groups can. Even though the S₁ pollen grains from group 1 can’t fertilise group 2’s stigma, the S₂ pollen grains can.

There are 22 compatibility groups and one special group, known as the universal donor or universal pollinator group. This group has a special allele called S₄’, or S₄ Prime, which is self-compatible. Trees in these groups are self-fertile and make excellent pollinators, because the S₄’ pollen grains will pollinate any stigma.

A self-sterile cherry can be intra-sterile or intra-fertile, depending on what it is paired with. Paired with a cherry in the same group, it is intra-sterile. Paired with one from a different group, it is intra-fertile. In the former case, you would receive no fruits as there is no pollination.

Cherries be completely incompatible, partially compatible (where one allele can pollinate) and totally compatible (where both alleles can pollinate). Even universal pollinators aren’t always totally compatible with other cherries as the non-S₄’ allele may match the allele in another variety.

Other Factors Affecting Pollination

Temperature: high temperatures raise the growth rate of the pollen tube, accelerating fertilisation, but also decrease the life of the ovule. Low temperatures slow the growth of the pollen tube, slowing fertilisation, and reduce foraging by honeybees, the principal pollinator of plants.

Precipitation: rainfall stops the flight activity of bees. Bees fly only short distances between showers.

Wind: wind reduces flying speed as well as the number of flights per day.

Nutrients: deficiencies in nitrogen, boron and zinc all negatively affect pollination. Nitrogen affects bud size and strength and the longevity of the ovule, while boron affects pollen viability and speed of germination as well as the speed of pollen tube growth. Deficiencies in zinc reduces fruit set.

Nearby Plants: it is a little known fact that the colour of the first flower a bee lands will be its perference thereafter. Bees are also attracted to purple/blue flowers on which there is the highest concentration of nectar. Bees may forgo pale white cherry flowers for more vivid flowers. It’s therefore unwise to plant species like lavender near your fruit orchard.

–

Jorge works in the Primrose marketing team. He is an avid reader, although struggles to stick to one topic!

His ideal afternoon would involve a long walk, before settling down for scones.

Jorge is a journeyman gardener with experience in growing crops.